- Introduction To Mutual Funds

- Funding Your Financial Plans

- Reaching Your Financial Goals

- Understanding Money Market Fund

- Understanding Bond Funds

- Understanding Stock Funds

- Know What Your Fund Owns

- Understanding The Performance Of Your Fund

- Understand The Risks

- Know Your Fund Manager

- Assess The Cost

- Monitoring Your Portfolio

- Mutual Fund Myths

- Important Documents In A Mutual Fund

- Study

- Slides

- Videos

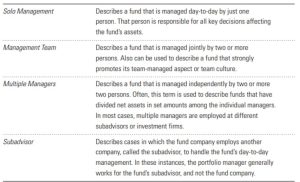

10.1 Types of Fund Management

Before you can judge the quality of your manager, you need to know the three types of fund management. The most straightforward way is the single-manager approach. These are the managers who, like Fidelity’s Peter Lynch, become the stars of the fund industry. However, even a sole manager seldom works in total isolation. They get plenty of market research and stock ideas from the stock analyst staff.

Then there’s the management team, popularized by fund companies like HDFC Mutual Fund and Axis Mutual Fund. The team may consist of two or more comanagers who work together to select the fund’s portfolio holdings. Sometimes one manager will make the final call on what to buy or sell, or each manager may have greater say about investments that land in his or her area of specialization. In other cases, the process is more democratic and each manager has equal say.

Finally, and much less common than the other two, is the multiple manager system. In this system, a fund’s assets are divided among a number of managers who work independently of each other. The multimanager approach is becoming more common because of so-called all-star funds such as those offered under the Managers and Masters’ Select names. Those funds hire name-brand managers from different fund groups and portion out assets among them. These hired guns are known as subadvisors.

10.2. Assessing Management

When savvy investors such as pension managers and consultants visit money managers, they focus their examination of the company on personnel. They look at the backgrounds of managers and analysts, examine the hiring process, dig into the way analysts and managers work together, and examine compensation systems.

With limited time and access, it’s not practical for most individual investors to go through the same due-diligence process, but you can learn most of what you need to know without flying out to visit management. Evaluating management-either of a company or a fund-is the point at which investing becomes more art than science. You won’t find management skill neatly summed up in a data point; you must use your judgment. By looking at a few key criteria, you can improve your portfolio’s performance, find managers who will stick around, and feel more comfortable about the funds in your portfolio.

Quality & Quantity of Experience

There’s no reason to settle for an inexperienced manager when there are hundreds of funds with skilled, seasoned management. Although you’ll often hear the claim that most fund managers are under the age of 40, the average manager is actually about 5 or 10 years older than that. In fact, most investors do have experienced managers working for them.

You can find a manager’s tenure at a fund company’s Web site or 5paisa mutual fund page. One-page fund report also contains information on other funds the manager runs. Check to see when and where the manager’s career in investing began and when he or she began managing money. A good rule of thumb is to search out managers who have logged at least 10 years as an analyst or manager and 5 years as a portfolio manager. If the fund manager previously ran other funds, take a good look at the records of those funds to see how they fared against others in their peer group.

Experience is not the only thing that matters, though. Where a fund manager learned about investing is as important as total tenure. Look for managers who learned to invest from great managers, or who cut their teeth at firms with lots of great funds. The manager might have come up through the ranks at a giant, high-quality firm like HDFC or ICICI, or somewhere in between.

Ownership of the Fund

One of the best ways to find a manager whose interests are aligned with yours is to find a fellow shareholder. Most managers have money in their funds, but they also have a lot at stake in their bonuses. A typical manager might have 25 lakh invested in his or her fund, but stands to pocket a 1cr in bonus if it crushes its peer group. Naturally, that manager has a big incentive to take the risks necessary to produce big returns. Meanwhile, the manager probably doesn’t even know what his or her fund’s tax position is because the firm’s bonus system is based on pretax returns.

Now consider a less common example: A manager has 50cr invested of his own money invested in his fund. With a king’s ransom in the fund, that manager has a powerful incentive to stay focused on long-term returns and capital preservation. A bonus can’t sway that. In addition, the chances are pretty low that the manager will be tempted to jump ship. On top of that, he’ll be very tax conscious because capital gains distributions would cost him millions in taxes. Not many managers have that kind of loot in their funds, but it’s worth the effort to track a couple of them down.

Finding out how much a manager has invested in the fund can be tricky. When it comes to their investments, fund managers don’t have to tell you a thing. You won’t get a peep out of the ones who have only a token investment in their funds, but the ones with fortunes in their funds are generally happy to share that information.

10.3. Dealing with the changes

Knowing who runs your fund is important, but what happens if your manager leaves? Is your fund an automatic sell candidate? Maybe in some cases. Most of the time, a management change is not cause for panic. A study found that strong-performing funds generally stay ahead of the pack after a management change, whereas weak performers tend to keep lagging.

When a Management Change Isn’t Cause for Concern-and When It Is

Based on what we’ve learned over the years, here are some examples of when investors generally should sit tight following a management change:

- If you own a fund from a category with modest variation in returns– Successfully managing a bond fund is a matter of gaining fractions of a percentage point in returns. Returns within a category of bond funds usually don’t vary much. For example, in 200, short-term government bond funds gained an average of 7%. Two-thirds of the funds in that group had returns between 6% and 8%. Unless your manager is so exceptionally good or bad as to reliably deliver returns outside that mass, a management change isn’t likely to mean much.

- If a fund family has a strong bench– When a fund manager leaves HDFC Or Axis, you usually don’t get too worked up about it. Why not? HDFC has scores of talented managers and analysts who can take up the slack.

- If your fund uses a team-managed or multiple manager approach. Team managed and multimanager funds where the team really did work democratically are least likely to be affected by the departure of a single individual.

If your fund’s new manager has racked up a strong record elsewhere- In this case, you want to be sure that the firm has also brought aboard the new manager’s whole staff-not just one individual. That might sound odd, but it happens frequently when fund companies hire outside money management firms called subadvisors instead of hiring their own investment professionals directly.

Although selling immediately is usually not the best course of action, keep a close eye on manager changes in the following situations:

- If your fund hails from a firm that has just a handful of funds. Replacing the departing manager may stretch resources pretty thin.

- If your fund happens to be the one good one among a group of poor ones. This holds true whatever the fund family’s size

- If your fund is run by a single manager. This is particularly a concern for funds at smaller shops.

- If your manager’s skill at selecting stocks has been key to the fund’s performance.

- If your fund resides in a category such as small-cap growth or emerging markets, where the range of returns is broad.