- Study

- Slides

- Videos

2.1 Evolution Of Exchange Rate System

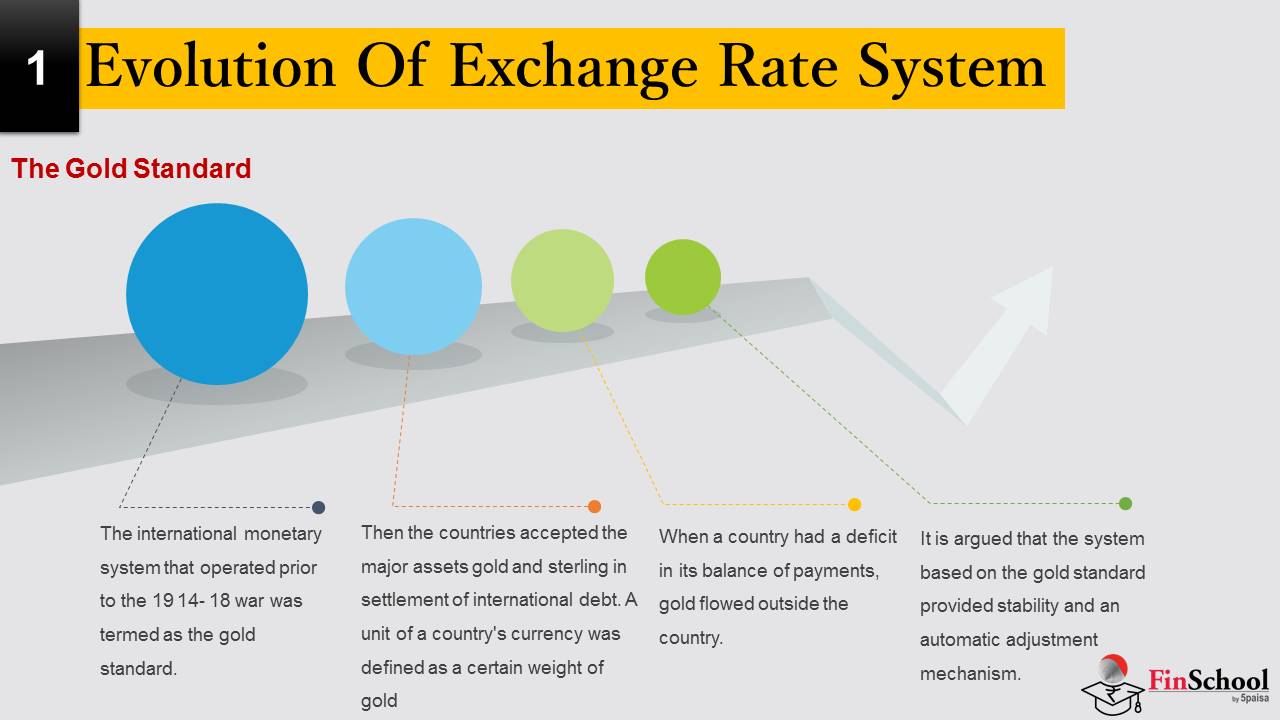

The Gold Standard-

The international monetary system that operated prior to the 19 14- 18 war was termed as the gold standard. Then the countries accepted the major assets gold and sterling in settlement of international debt. A unit of a country’s currency was defined as a certain weight of gold (e.g. a pound sterling could be converted into 113.0015 grains of fine gold and the U.S. dollar into 23.22 grains. Through these gold equivalents, the value of the pound was 113.0015 / 23.22 times, (or 4.885 times that of the dollar. Thus 4.885 dollars was the ‘par value’ of the pound)

A country is said to be on the gold standard when its central bank is obliged to give gold in exchange for its currency when presented to it. The gold standard was the foundation of the international trading system. The currency of a country was freely convertible into gold at a fixed exchange rate. lnternational debt settlement was to be in gold. When a country had a surplus in its balance of payments, gold flowed into its central bank. Thus the country with a balance of payments surplus could expand its domestic money supply without having the fear of insufficient gold to meet its liabilities. When the money supply increased, prices increased, hence the demand of exports fell, the balance of payments surplus was reduced. On the other hand, when a country had a deficit in its balance of payments, gold flowed outside the country. Thus the deficit country had to contract the money supply with the reduction in its gold stocks. ‘The prices of commodities decreased. Its exports become more competitive and the deficit automatically got corrected, as increase in exports resulted in gold Mows.

It is argued that the system based on the gold standard provided stability and an automatic adjustment mechanism. Since the value of gold relative to other goods and services does not change much over long periods of time, the monetary discipline imposed by the gold standard was expected to ensure long-run price stability.

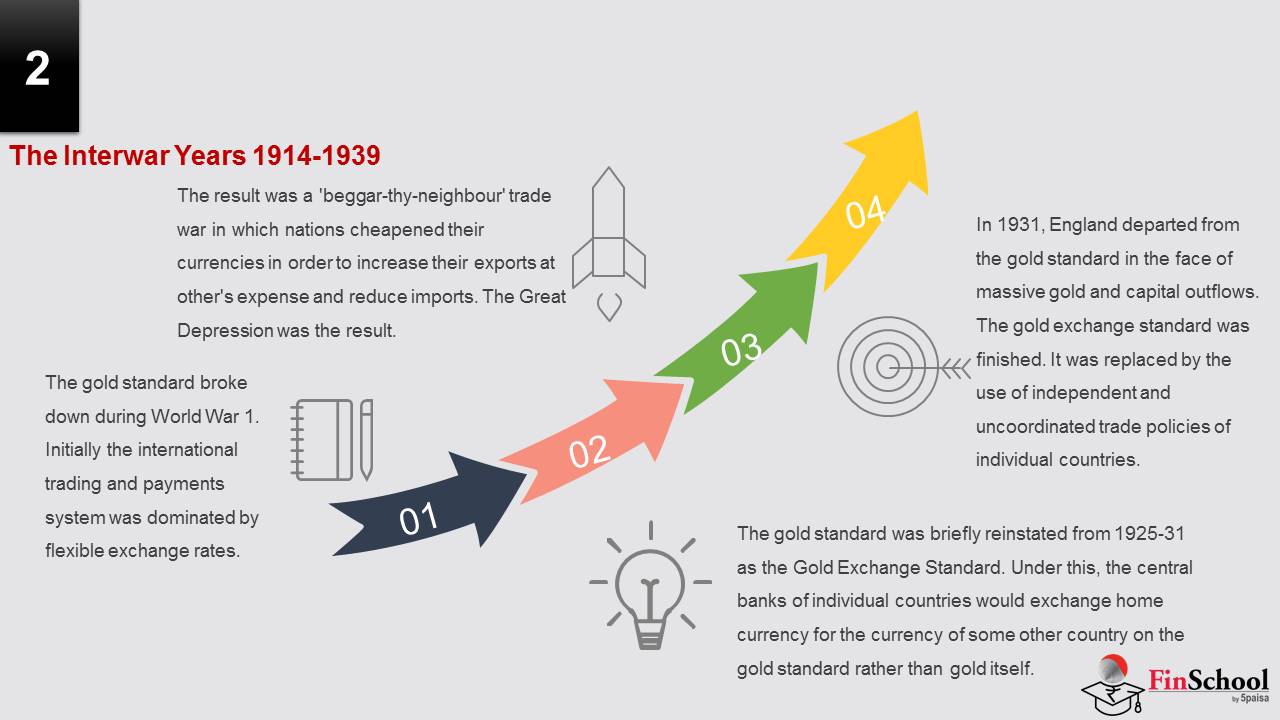

The Interwar Years 1914-1939

The gold standard broke down during World War 1. Initially the international trading and payments system was dominated by flexible exchange rates. ‘The gold standard was briefly reinstated from 1925-31 as the Gold Exchange Standard. Under this, the central banks of individual countries would exchange home currency for the currency of some other country on the gold standard rather than gold itself. In 1931, England departed from the gold standard in the face of massive gold and capital outflows. The gold exchange standard was finished. It was replaced by the use of independent and uncoordinated trade policies of individual countries. These included managed exchange rates: devaluations of currencies and protectionism. The result was a ‘beggar-thy-neighbour’ trade war in which nations cheapened their currencies in order to increase their exports at other’s expense and reduce imports. The Great Depression was the result. Output ‘and employment levels in individual countries came down for a decade.

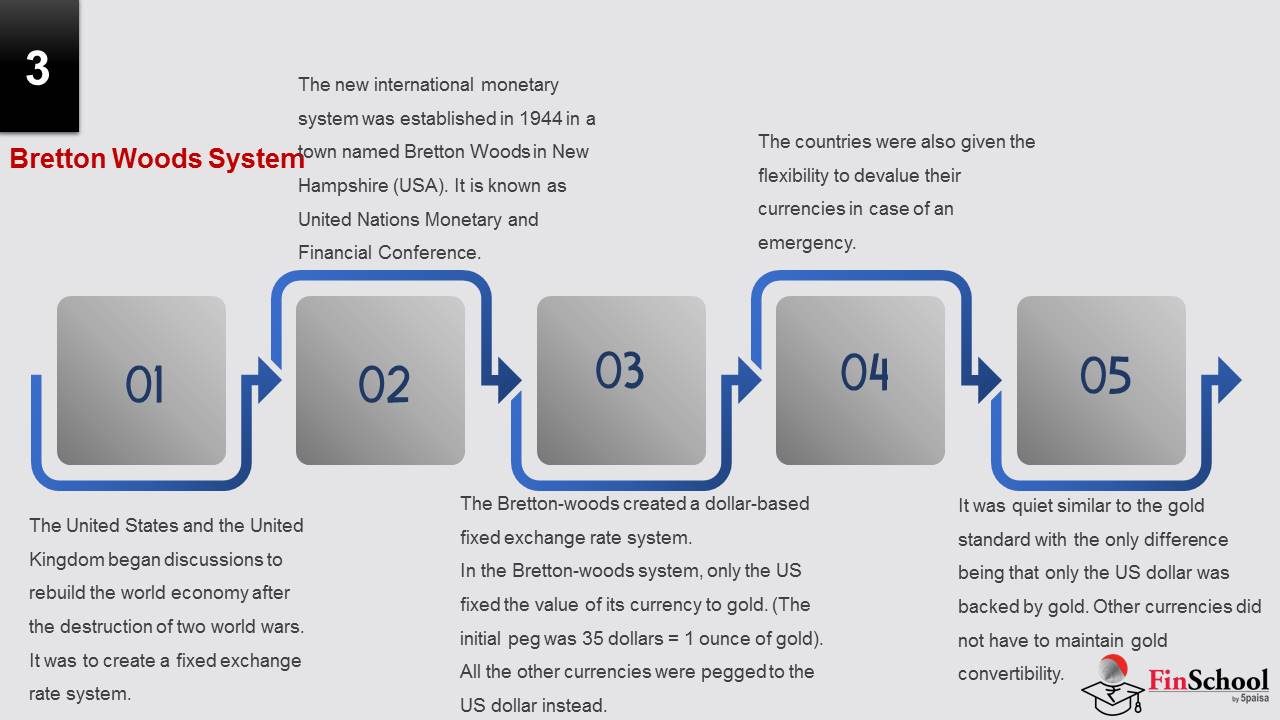

Bretton Woods system

In the early 1940s, the United States and the United Kingdom began discussions to rebuild the world economy after the destruction of two world wars. Their goal was to create a fixed exchange rate system without the gold standard.

The new international monetary system was established in 1944 in a conference organised by the United Nations in a town named Bretton Woods in New Hampshire (USA). The conference is officially known as the United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference. It was attended by 44 countries.

The Bretton-woods created a dollar-based fixed exchange rate system.

In the Bretton-woods system, only the US fixed the value of its currency to gold. (The initial peg was 35 dollars = 1 ounce of gold). All the other currencies were pegged to the US dollar instead. They were allowed to have a 1 % band around which their currencies could fluctuate.

The countries were also given the flexibility to devalue their currencies in case of an emergency.

It was quiet similar to the gold standard with the only difference being that only the US dollar was backed by gold. Other currencies did not have to maintain gold convertibility.

Also, this convertibility was limited. Only governments (not anyone who demanded it) could convert their US dollars into gold.

Collapse of Bretton Woods System:

In 1971, concerned that the U.S. gold supply was no longer adequate to cover the number of dollars in circulation, President Richard M. Nixon declared a temporary suspension of the dollar’s convertibility into gold. By 1973 the Bretton Woods System had collapsed. Countries were then free to choose any exchange arrangement for their currency, except pegging its value to the price of gold. They could, for example, link its value to another country’s currency, or a basket of currencies, or simply let it float freely and allow market forces to determine its value relative to other countries’ currencies.

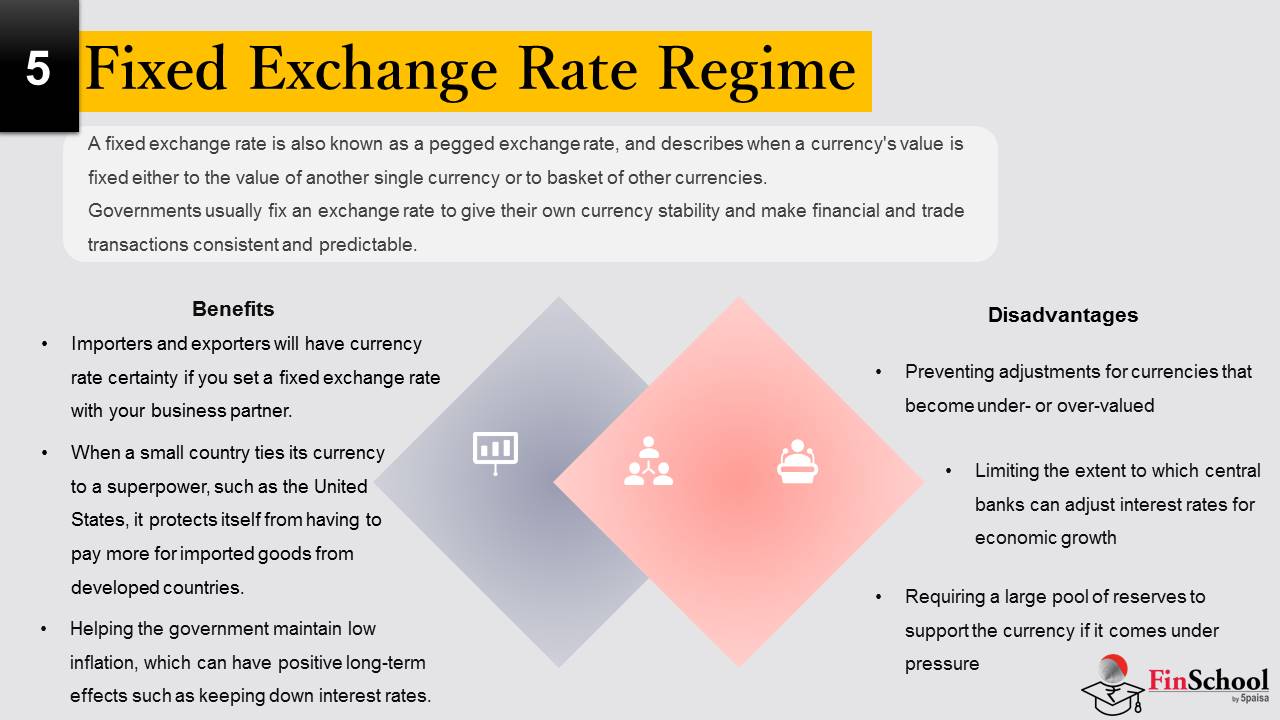

2.2 Fixed Exchange Rate Regime

A fixed exchange rate is also known as a pegged exchange rate, and describes when a currency’s value is fixed either to the value of another single currency or to basket of other currencies. This means if you make multiple exchanges between these currencies you’ll always get the same exchange rate and so the same value for your money.

The purpose of a fixed exchange rate system is to keep a currency’s value within a narrow band. Governments usually fix an exchange rate to give their own currency stability and make financial and trade transactions consistent and predictable.

Examples of fixed exchange rates

Currencies with fixed exchange rates are usually pegged to a more stable or globally prominent currency, such as the euro or the US dollar.

For example, the Danish krone (DKK) is pegged to the euro at a central rate of 746.038 kroner per 100 euro, with a ‘fluctuation band’ of +/- 2.25 per cent.

This means that the euro to DKK exchange rate must be with 2.25% of the central rate and can’t drop below 729.252 DKK per 100 euro or exceed more than 762.824 per 100 euro.

The Benefits of Having a Fixed Exchange Rate

- Importers and exporters will have currency rate certainty if you set a fixed exchange rate with your business partner.

- When a small country ties its currency to a superpower, such as the United States or the European Union, it protects itself from having to pay more for imported goods from developed countries. When the US economy expands, the currency appreciates, making imports more expensive for smaller countries. As a result, a fixed exchange rate protects them from such dangers.

- Helping the government maintain low inflation, which can have positive long-term effects such as keeping down interest rates

Disadvantages of fixed exchange rate system

- Preventing adjustments for currencies that become under- or over-valued

- Limiting the extent to which central banks can adjust interest rates for economic growth

- Requiring a large pool of reserves to support the currency if it comes under pressure

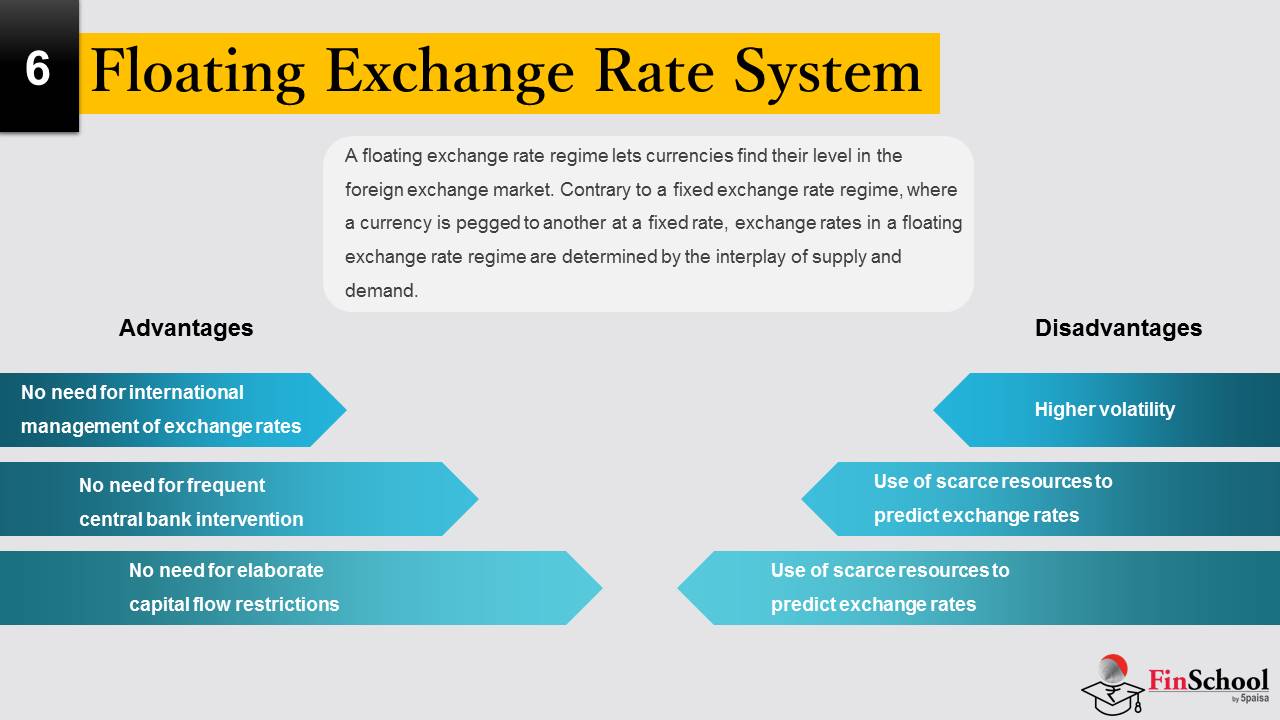

2.3 Floating Exchange Rate System

A floating exchange rate regime lets currencies find their level in the foreign exchange market. Contrary to a fixed exchange rate regime, where a currency is pegged to another at a fixed rate, exchange rates in a floating exchange rate regime are determined by the interplay of supply and demand.

A floating exchange rate is not restrained by trade limits or government controls. They work through an open market system in which the price is driven by speculation and the forces of supply and demand. Under this system, increased supply but lower demand means that the price of a currency pair will fall; while increased demand and lower supply means that the price will rise.

Floating currencies are perceived as strong or weak depending on the market sentiment towards their country’s economy. For example, if a government is viewed as unstable, the currency is likely to depreciate as faith in their ability to regulate the economy declines.

However, governments can intervene in a floating exchange rate to keep their currency’s price at a favorable level for international trade – this also helps to avoid manipulation by other governments.

Advantages of Floating Exchange Rate system:

- No need for international management of exchange rates: Unlike fixed exchange rates based on a metallic standard, floating exchange rates don’t require an international manager such as the International Monetary Fund to look over current account imbalances. Under the floating system, if a country has large current account deficits, its currency depreciates.

- No need for frequent central bank intervention: Central banks frequently must intervene in foreign exchange markets under the fixed exchange rate regime to protect the gold parity, but such is not the case under the floating regime. Here there’s no parity to uphold.

- No need for elaborate capital flow restrictions: It is difficult to keep the parity intact in a fixed exchange rate regime while portfolio flows are moving in and out of the country. In a floating exchange rate regime, the macroeconomic fundamentals of countries affect the exchange rate in international markets, which, in turn, affect portfolio flows between countries. Therefore, floating exchange rate regimes enhance market efficiency.

Disadvantages:

- Higher volatility: Floating exchange rates are highly volatile. Additionally, macroeconomic fundamentals can’t explain especially short-run volatility in floating exchange rates.

- Use of scarce resources to predict exchange rates: Higher volatility in exchange rates increases the exchange rate risk that financial market participants face. Therefore, they allocate substantial resources to predict the changes in the exchange rate, in an effort to manage their exposure to exchange rate risk.

- Use of scarce resources to predict exchange rates: Higher volatility in exchange rates increases the exchange rate risk that financial market participants face. Therefore, they allocate substantial resources to predict the changes in the exchange rate, in an effort to manage their exposure to exchange rate risk.

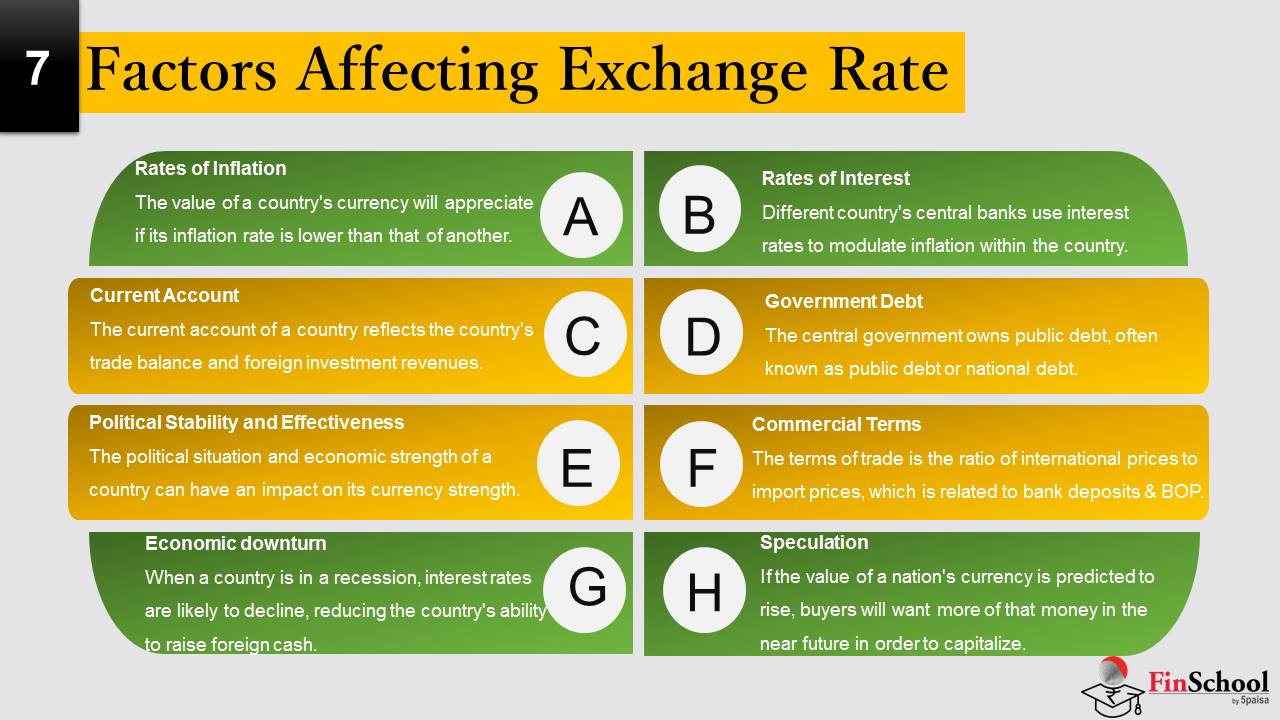

2.4 Factors Affecting Exchange Rate

Currency exchange rates are affected by changes in market inflation. The value of a country’s currency will appreciate if its inflation rate is lower than that of another. When inflation is low, prices of goods and services rise at a slower pace. A country with a consistently lower inflation rate sees its currency appreciate, whereas a country with higher inflation sees its currency depreciate, which is often coupled by higher interest rates.

Rates of Interest

Interest rates are tightly tied to inflation and exchange rates. Different country’s central banks use interest rates to modulate inflation within the country. For example, establishing higher interest rates attracts foreign capital, which bolsters the local currency rates. However, if these rates remain too high for too long, inflation can start to creep up, resulting in a devalued currency. As such, central bankers must consistently adjust interest rates to balance benefits and drawbacks.

Current Account / Balance of Payments of the Country

The current account of a country reflects the country’s trade balance and foreign investment revenues. It is made up of the entire number of transactions, such as exports, imports, debt, and so on. A current account deficit occurs when a country spends more of its currency on goods imported than it earns.

Government Debt

The central government owns public debt, often known as public debt or national debt. Government debt makes a country less likely to attract foreign capital, resulting in inflation. If the market expects that a country’s public debt will default, foreign investors will sell their bonds on the open market. As a result, the value of the currency’s exchange rate will fall.

Commercial Terms

The terms of trade is the ratio of international prices to import prices, which is related to bank deposits and balance of payments. If a country’s export prices rise faster than its import prices, its terms of trade increase. This leads to increased revenue, which in turn leads to increased demand for the country’s currency and a rise in its value. As a result, the exchange rate appreciates.

Political Stability and Effectiveness

The political situation and economic strength of a country can have an impact on its currency strength. As a result, a country with a lower risk of political unrest is more appealing to foreign investors, attracting capital away from countries with greater macroeconomic stability. An inflow of foreign capital leads to a rise in the value of the country’s currency. A country with good financial and trade policies does not allow for any uncertainty in its currency’s value. However, if a country is prone to political unrest, exchange rates may depreciate.

Economic downturn

When a country is in a recession, interest rates are likely to decline, reducing the country’s ability to raise foreign cash. As a result, its economy depreciates against the currencies of other countries, depressing the exchange rate.

Speculation

If the value of a nation’s currency is predicted to rise, buyers will want more of that money in the near future in order to capitalize. As a result of the increased demand, the currency’s value will grow. The exchange rate rises in line with rising in currency value.